DAYLIGHTING FOR SUSTAINABILITY

LEARNING FROM VERNACULAR

CASE STUDY: Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar

November 2022

Abstract

By looking at history and the first approaches for sustainability and learning from the vernacular architecture, a modern architectural heritage, Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar, will be analyzed to develop ideas on how the sustainability role of lighting design in today's building can be constructed.

Introduction

Manufacturers are in competition to be in the stage of energy-saving, sustainable solutions for the lighting design industry. Every year, a new product is manufactured with the promise of energy efficiency. Artificial lighting seems to be trying its best to be in the market. But using artificial lighting efficiently might not be enough for energy saving and sustainability. Although their efficacy is improved, they still use electricity and energy. What might help to double the efficiency is to bring daylight back to the scene as used in vernacular architecture in history when there wasn’t common artificial light use and learn from them in terms of the relation between daylight and the architectural space. By learning how to control the daylight, we can bring daylight back to the design process rather than making artificial lighting decisions the main solution for sustainability. In a world of spreading constructions, some action should be taken to the awareness of sustainability and daylight.

Sustainability

“Sustainability”, “green”, “eco”, and “environmentally friendly” have been used as words more than the potency of their meaning for years but their actual importance started to show themselves recently in every field with the peak in energy crisis and environmental change. What sustainability actually means matters to understand what to be aware of during this crisis and to know how actions should be taken.

United Nations defined sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of the future generation to meet their own” in 1987 as a World Commission Environment and Development report firstly. Today in 2022, the word “sustainability” is used to strengthen the promises of companies, politicians, individuals, and manufacturers. After 35 years, we are still slogging on not taking more actions instead of speaking with these fancy words. Although there are some young voices made themselves heard, some small, individual actions were taken, and some of the companies seemed to be more conscious, there is still a huge gap between where we are and where we should reach in terms of energy savings and sustainability. Professional endeavors should be included in the process of understanding sustainability and taking action as much as individual endeavors. Thus we can get a little closer to our goal with this awareness in our professions as architects, urban planners, interior designers, and lighting designers. We should know what sustainability means and how to integrate it into our professions.

Even though sustainability is mostly associated with being sustainable in terms of energy, it actually has three dimensions economic, environmental, and social. We have to be aware of how any intervention we make affects all these different areas in order to talk about actual sustainability which can be achieved by implementing the four Rs: reduce, reuse, recycle, and regenerate. (Lechner, 2009)

Sustainability in Lighting Design

Conventional light sources will reach out by 2023 and what will replace these sources would be the LEDs. (licht.de) It should be also questioned if it will be enough to save energy by changing all of the conventional light sources to super-efficient LEDs.

Figure 1. Phasing out of conventional Light Sources

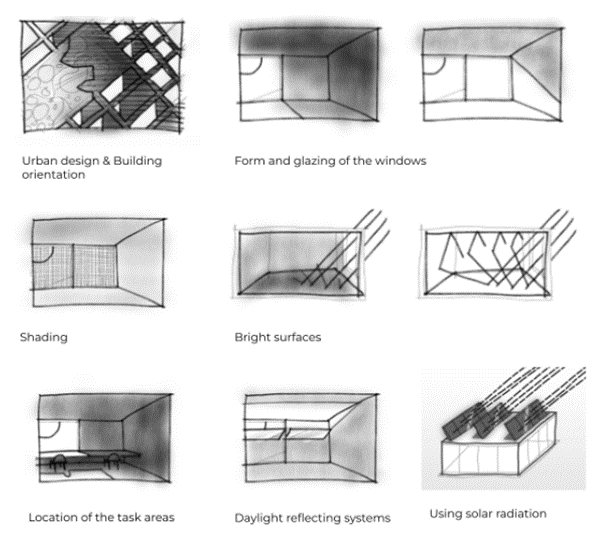

Awareness of energy saving and consciousness for sustainability should be more than using artificial lighting efficiently. Artificial light should also be designed and controlled. Designing the lighting overall with the building, its location, its functions, its form, time of use, and material choice play an important role in energy saving.

Figure 2. 7 Ways Lighting Can Make Architecture More Sustainable (Schilke, 2014)

Figure 3. Erco Parscan

The lighting manufacturer ERCO is aiming to create flexibility for their luminaires to be used in different scenarios of the space that is illuminated. They are providing a base luminaire with a variety of lenses, honeycombs, color filters, and controllers that can easily be mounted to the base. Their aim is to increase the usability of the luminaire by increasing the mounting possibilities to fulfill different needs. However, achieving the consciousness of the sustainability for luminaire itself is not enough. Not only the luminaire but how it is produced, and how it is used also matters in terms of sustainability. How all the components that promise flexibility are produced, how recyclable the materials are, how much energy is consumed for their production of them, and how the luminaires are shipped to the project sites should also be taken into consideration. While there are lots of parameters in the process of the production of artificial light sources in terms of energy saving, and sustainability, one option to enhance the sustainability approach also could be decreasing artificial light use as much as possible. As also defined by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory NREL, “Indoor illumination provided by natural light entering the space through some type of fenestration that results in a reduction of necessary electrical lighting for ambient, accent, emergency, or task lighting.”

What can decrease the use of artificial light and save energy is to know how daylight works in a building and imply it to the design process. Daylight control should go hand to hand with artificial lighting for creating illumination and thermal comfort in the space.

There are two conditions for us to be conscious designers. First is that we need to consider all the parameters of sustainability in the earliest stage of the design process for the buildings that will be constructed and the second is how we can integrate this awareness into the already existing architectural space. Methods for achieving this may vary for these two different conditions. This paper will mainly focus on how sustainability should be taken into consideration in the earliest stage of the design process by looking at and learning from the vernacular architecture and other types of architecture that are designed with daylight in relation to sustainability and analyzing a case study building with the information provided.

Daylight

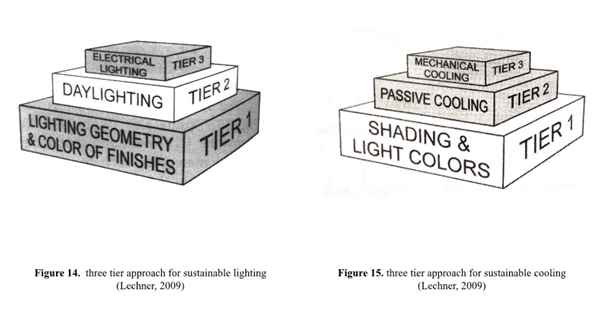

Lechner, defines sustainable lighting design with three main approaches that are conducted as a three-tier pyramid. The largest and most important tier refers to the basics of the design of the architectural space (lighting geometry, color of finishes), the second larger one is passive systems which include daylighting and the last one is mechanical and electrical equipment (electrical lighting).

By using sunlight and daylight in the correct way, total energy consumption (electrical lighting, heating and cooling, and others) can be reduced. We can see them as an environmental and economic approach to sustainability. If we would also like to think about the social sustainability point of view, we can also see the effects of daylight on the people who are the users of the space since daylight has a huge impact on human health physically and psychologically.

We can approach economical, environmental, and social sustainability by integrating daylight into the designed environment.

Figure 4. 7 Ways Daylight Can Make Design More Sustainable (Schilke, 2014)

From vaults in Roman architecture to Crystal Palace, the architecture was shaped by the decision of increasing the daylight in interior space in the absence of artificial light as the main source. (Lechner, 2009)

Not only the single building types but also the settlements and urban places were designed in a way to get the best efficiency of daylight.

With the urban renovation projects in Turkey, which could exist for economic and political reasons rather than necessity, cities have become unplanned and buildings have started to lose their livability. Daylight availability is one of the things which were ignored in the design process of the super-growing construction sector. We can see the results of this unconsciousness in the buildings and how they affected their surroundings in the urban context. To be able to speak of sustainability, we should also be aware of how a building affects its surroundings in addition to conscious design actions towards a building.

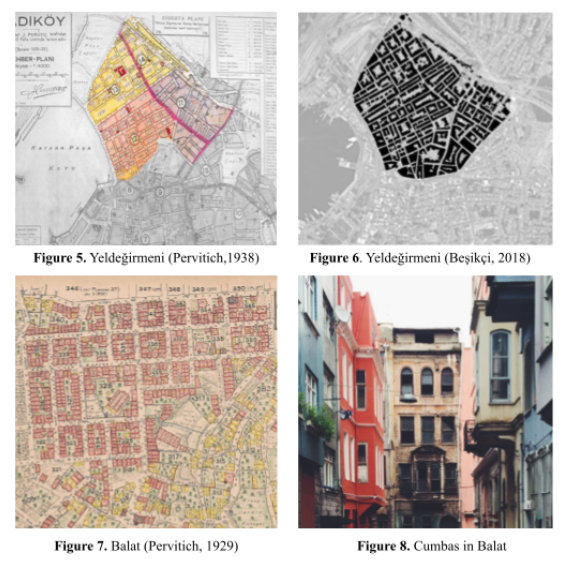

In Istanbul, one of the cities most affected by the urban renovation, it is possible to see residential areas which are under preservation like Yeldeğirmeni, and Balat that have not been affected by this phenomenon. The urban structure created with a grid plan can clearly be seen. Detached buildings are located in this grid with the inner courtyard. This type of urban structure created with the respect to the urban scale and urban context can help to increase the daylight availability for the inner - courtyard-facing facades of the buildings.

Cumbas (bay windows) which are one of the important elements of traditional residential architecture in Anatolia is also one of the main futures of the buildings in these neighborhoods. While these cumbas give mobility to the street texture and the sight out of the building, also provide control of light and increase the air ventilation in the interior space. (Aydın, Y.C., Mirzaei, P.A., 2017)

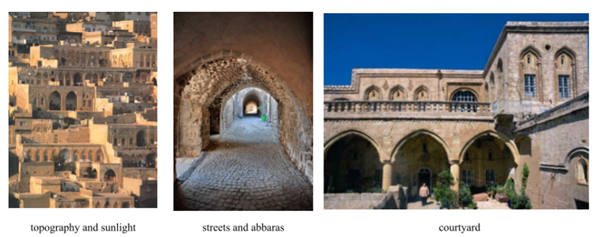

The city of Mardin which is located in the south-east region of Turkey can be given as an example to look in detail at the relationship between the courtyard configuration and daylight availability since the main characteristic of the architecture is created mainly with the climatic conditions of the city that has a hot and dry climate. Even on hot summer days, it is possible to walk on the narrow streets of Mardin thanks to the shadows that are created by the surrounding buildings and closed passages on the streets. Mardin is located in a sloped area. The buildings, which are placed in accordance with the topography, do not block each other's daylight and view. Open and semi-open spaces are provided in the urban texture such as terraces, iwans, riwaqs, and courtyards that play an important role in daylight and thermal comfort. (Sayigh, Marafia, 1998)

The city of Mardin which is located in the south-east region of Turkey can be given as an example to look in detail at the relationship between the courtyard configuration and daylight availability since the main characteristic of the architecture is created mainly with the climatic conditions of the city that has a hot and dry climate. Even on hot summer days, it is possible to walk on the narrow streets of Mardin thanks to the shadows that are created by the surrounding buildings and closed passages on the streets. Mardin is located in a sloped area. The buildings, which are placed in accordance with the topography, do not block each other's daylight and view. Open and semi-open spaces are provided in the urban texture such as terraces, iwans, riwaqs, and courtyards that play an important role in daylight and thermal comfort. (Sayigh, Marafia, 1998)

- The air of summer night is kept in the courtyard for a long period of time

- The rooms receive daylight and air from the courtyard.

- Ventilation is provided.

- Gentle microclimate is provided in the courtyard for outdoor use.

Figure 9. Mardin (Aydın, 2009)

Figure 10. Site section, (Alioglu, E, F. 2000)

Figure 11. Microclimate and climate in Mardin (Akın, Yıldırım, 2020)

The Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar

By learning from the examples of the vernacular architecture, a building in Eminönü, İstanbul will be analyzed in terms of sustainability. Even though there is a need to measure all of the parameters such as daylight availability, thermal comfort, and glare more detailed in an advanced simulation program to get a better understanding and result, the analysis will be done by studying the location, orientation, form, material choice, typology of the building within the scope of this paper and only one unit will be analyzed through online software which was introduced by Andrew Marsh. . It is also aimed that this paper will be a guide for further studies that question the role of natural and artificial lighting in the re-publicisation of the less-active modern heritage buildings like the Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar.

By learning from the examples of the vernacular architecture, a building in Eminönü, İstanbul will be analyzed in terms of sustainability. Even though there is a need to measure all of the parameters such as daylight availability, thermal comfort, and glare more detailed in an advanced simulation program to get a better understanding and result, the analysis will be done by studying the location, orientation, form, material choice, typology of the building within the scope of this paper and only one unit will be analyzed through online software which was introduced by Andrew Marsh. . It is also aimed that this paper will be a guide for further studies that question the role of natural and artificial lighting in the re-publicisation of the less-active modern heritage buildings like the Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar.

History and Architecture

The Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar is a building designed by the architects Dogan Tekeli, Sami Sisa, and Metin Hepgüler as the winner of the competition held in 1960 to find the design for a shopping area for the needs of the Istanbul Textile and Fabric Shop Building Cooperative. It is one of the most important buildings in Turkey in terms of being an example of modern architecture in the 1950s.

The main idea of the project was to blend the architecture with the existing context and the history of the space while referring to the vernacular bazaar typology of İstanbul.

Today

About The Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar, one of the buildings that hosted the 10th International Istanbul Biennial, the curator of the biennial, Hou Hanru, described the building as a small universe of Istanbul with the ever-expanding and transforming structure. (Altuğ, 2007) Although the building is located in an important urban, economic, and touristic location, over time, it began to lose the splendor planned for it. The building was even under threat of demolition in 2007. Nevertheless, thankfully it still functions as a shopping area and music production center despite the low demand compared to its past. With good planning and minor interventions, the building can be brought back to life at the local and urban levels.

Sustainability

The building has the potential to make a great contribution to its surroundings with small interventions and definitions by analyzing its problems, needs, current and potential users, and current relations with its surroundings. The building can contribute to the economy as a shopping and trade center which was the first character of the building; to the social structure with the relationship that it will establish with the surrounding local texture, to tourism with the historical value and potential itself and its location, and to education with its potential to be integrated with the educational building, which is one of the surrounding public buildings.

One of the steps to be taken in the name of sustainability is to analyze the potential of the existing situation and develop solutions for it, instead of destroying it.

In this stage, as in many professions, lighting design has an important role in the process of analyzing the problems and potentials, the process of producing solutions, and the possible future effects of the interventions that are made.

Sunlight and daylight in the building can decrease the use of artificial lighting, and heating. However, while we try to take advantage of them we should not avoid the potentially negative effects. When they are used as a lighting source and solar radiation source of the building, they should be controlled to avoid glares and overheating in the space. Sustainable lighting and sustainable method for thermal comfort are defined by Lechner as a three-tier approach. Lighting geometry and shading are the key strategies for lighting and thermal comfort respectively. What comes later is daylighting and passive cooling as the second important strategy.

The Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar is a building designed by the architects Dogan Tekeli, Sami Sisa, and Metin Hepgüler as the winner of the competition held in 1960 to find the design for a shopping area for the needs of the Istanbul Textile and Fabric Shop Building Cooperative. It is one of the most important buildings in Turkey in terms of being an example of modern architecture in the 1950s.

The main idea of the project was to blend the architecture with the existing context and the history of the space while referring to the vernacular bazaar typology of İstanbul.

Today

About The Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar, one of the buildings that hosted the 10th International Istanbul Biennial, the curator of the biennial, Hou Hanru, described the building as a small universe of Istanbul with the ever-expanding and transforming structure. (Altuğ, 2007) Although the building is located in an important urban, economic, and touristic location, over time, it began to lose the splendor planned for it. The building was even under threat of demolition in 2007. Nevertheless, thankfully it still functions as a shopping area and music production center despite the low demand compared to its past. With good planning and minor interventions, the building can be brought back to life at the local and urban levels.

Sustainability

The building has the potential to make a great contribution to its surroundings with small interventions and definitions by analyzing its problems, needs, current and potential users, and current relations with its surroundings. The building can contribute to the economy as a shopping and trade center which was the first character of the building; to the social structure with the relationship that it will establish with the surrounding local texture, to tourism with the historical value and potential itself and its location, and to education with its potential to be integrated with the educational building, which is one of the surrounding public buildings.

One of the steps to be taken in the name of sustainability is to analyze the potential of the existing situation and develop solutions for it, instead of destroying it.

In this stage, as in many professions, lighting design has an important role in the process of analyzing the problems and potentials, the process of producing solutions, and the possible future effects of the interventions that are made.

Sunlight and daylight in the building can decrease the use of artificial lighting, and heating. However, while we try to take advantage of them we should not avoid the potentially negative effects. When they are used as a lighting source and solar radiation source of the building, they should be controlled to avoid glares and overheating in the space. Sustainable lighting and sustainable method for thermal comfort are defined by Lechner as a three-tier approach. Lighting geometry and shading are the key strategies for lighting and thermal comfort respectively. What comes later is daylighting and passive cooling as the second important strategy.

Analysis of the building

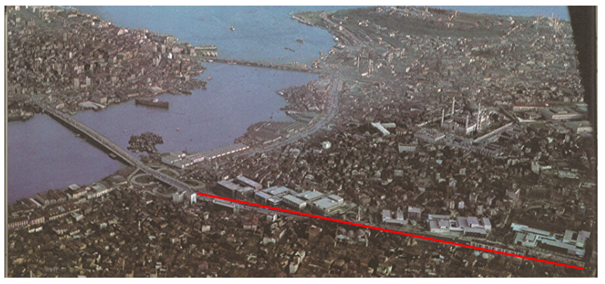

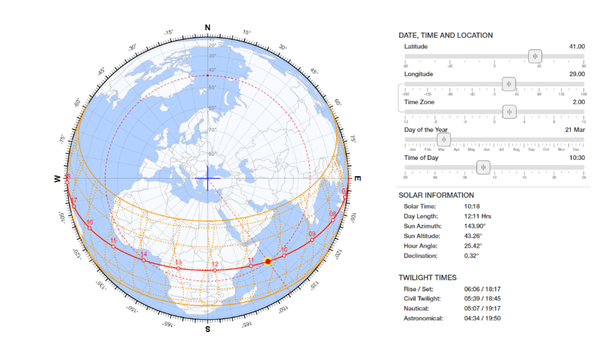

Location and orientation

The building is located in İstanbul, Turkey where the winters are long, cold, windy, and partially cloudy while the summers are warm, humid, dry, and clear.

Figure 16. The Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar and its surroundings

![]()

Figure 17. The Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar location

![]()

Figure 18. Sunpath of İstanbul (andrewmarsh.com)

![]()

Figure 19. Climate Data for İstanbul (andrewmarsh.com)

Figure 17. The Istanbul Drapers' and Furnishers' Bazaar location

Figure 18. Sunpath of İstanbul (andrewmarsh.com)

Figure 19. Climate Data for İstanbul (andrewmarsh.com)

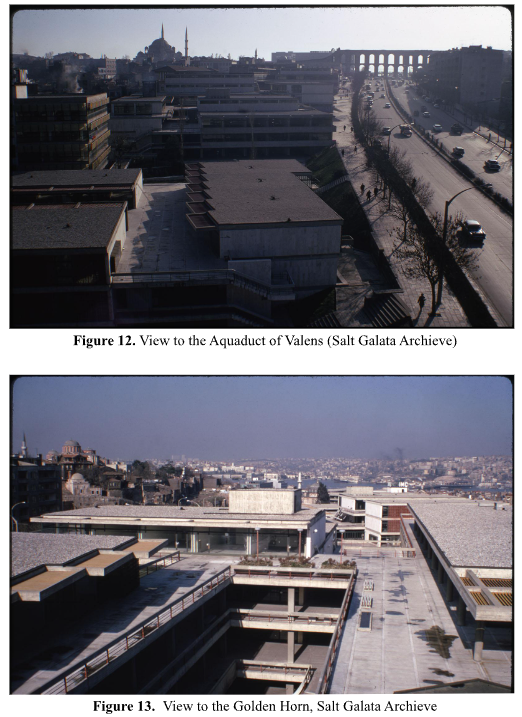

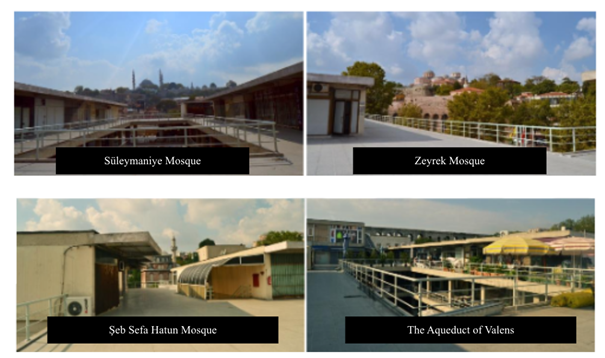

The form of the building defines the areas that will have access for daylighting. (Lechner, 2009) The masses of the buildings are located on the site as dynamic modules in harmony with the scale of the urban context. These masses that are located with different orientations on the sloped topography create courtyards and different visual terraces where Süleymaniye Mosque, Zeyrek Mosque, Şeb Sefa Hatun Mosque, and The Aqueduct of Valens can be seen.

Figure 20. Vista Points of the building

The orientation of the building matters in terms of the access to sunlight in the south orientation since more consistent sunlight is received by the building throughout the day and year and its heating effect can be used more efficiently in winter. (Lechner, 2009) The building that is analyzed in this paper is positioned at an angle of 54 degrees to the north. North-east and southwest facades were left solid. It is also possible to see different configurations of the facades in the same direction.

Figure 21. Facade Configuration (Salt Galata Archive)

The architects wanted to keep the idea of the street in the project. The continuous circulation through the whole building was important and it was provided with the continuity of the decks on the floors. The relation between the shops and the streets is provided between shops and courtyards on the upper floors. The user of the space is experiencing the street experience on the decks defined by the courtyards. These courtyards also provide daylight for the shops on different levels.

Figure 22. Sketch showing the continuous circulation (Salt Galata Archive)

Figure 23. View of the Courtyard (Salt Galata Archive)

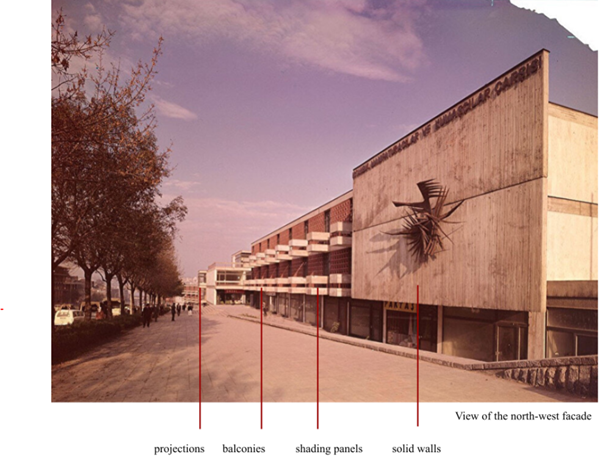

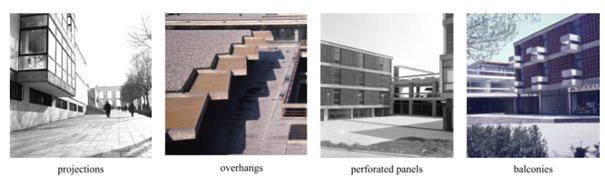

Projections, balconies, and perforated panels are used on the façade in order to decrease the scale of the whole building which was located horizontally on the site to respect the urban texture and not to create any dominance in the silhouette.

Figure 24. Sketch showing the relationship with the surroundings and Süleymaniye Mosque

(Salt Galata Archive)

Figure 25. Different elements of the building

(Salt Galata Archive)

Projections and overhangs

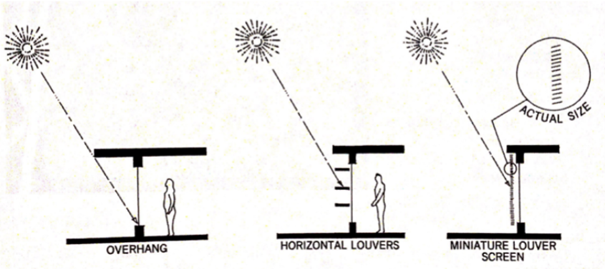

Shading effects may vary in terms of size and form but still can give a similar effect and control. However, overhangs are the best option to provide sight through the windows.

Figure 26. Different Shading Elements (Lechner, 2009)

Perforated Shading Panels

The perforations which are used to strengthen the horizontality of the façade, provide controlled sunlight in indoor areas of the shops.

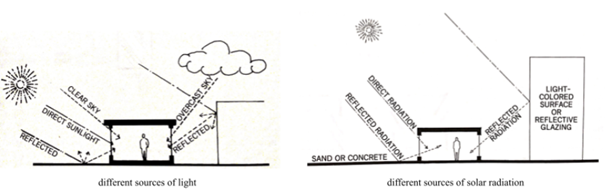

Windows

The window configuration of the building is important. There are different light sources entering through the window like direct sunlight, clear sky, reflections from the surrounding buildings as well as solar radiation as direct radiation and indirect radiation. The light color of the material in the building provides light to be reflected from the surroundings.

Figure 27. Different sources of light and solar radiation (Lechner, 2009)

The illumination just inside the wall is the greatest and this level rapidly decreases in the inner parts. About 1.5 times the height of the window defines the useful daylit area of the space. Compared to vertical windows, horizontal windows are better at creating uniformly distributed daylight. Since the depth of the shops is wide, there was a need for openings on both sides of the shop for receiving daylight. Avoiding unilateral windows and preferring bilateral windows, provide better light distribution and decreased glare.

Analysis of a shop unit located in the 5th block

The building has partially been changed due to the interaction with the user after it was built. The difference can be seen by comparing the old photos and design reports of the architects with the existing situation. One of the most visible differences in the facade comparisons is the missing perforated facade panels. It can be questioned if this interaction was made by the user due to the insufficient daylight efficiency of the shop although these changes were made overall the building and all of the panels were removed regardless of the orientation of the shop and its facade. Instead of the shading panels, shop signs are covering the facades. To be able to see the effect of these panels, one unit of the shops located in the 5th block was analyzed.

Figure 28. Comparison of the facades then and now (Salt Galata Archive)

Figure 29. Location of the analyzed block (earth.google.com)

Figure 30. Comparison of the analyzed block then and now

(Salt Galata Archive, google earth street view)

Figure 31. Simplified model of the block and the shop unit, south-east facade

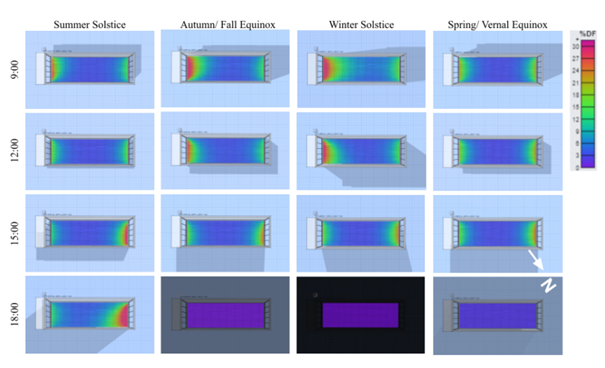

Figure 32. Dynamic Daylight Calculations (andrewmarsh.com)

Dynamic daylight was calculated for summer and winter solstices and equinoxes comparing different times in a day to be able to compare the daylight availability of the building throughout the year. The model was kept as the current situation today with an overhang on the southeast facade and removed shading panels. It can be seen that the values are high in the areas close to the windows in the southeast facade in winter and the northwest facade in summer in the mornings and in the afternoons respectively.

After seeing the results of different daylight availabilities of the shop throughout the year, it was aimed to see the effect of the different elements used in the building.

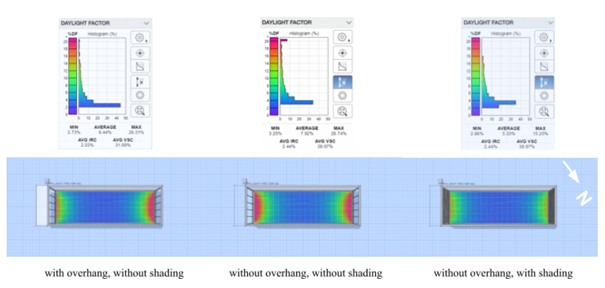

Figure 33. Daylight Factor Comparison (andrewmarsh.com)

Some analyses were made through the online software to see the effect of the overhang and shading panels on daylight in the indoor place using overcast sky conditions. Since the software does not allow to adjust of the windows separately, the calculation was made with shading panels in both facades in the scenario where shadings are used and overhangs are not. Overall in the three scenarios, the daylight factor is more than %2 in half of the room. Daylight factor in the areas close to the windows differs with the use of overhangs and shading panels and reaches up to %20 when none of them are used in the building.

Figure 34. Spatial Daylight Autonomy and Sunlight Exposure (andrewmarsh.com)

Spatial daylight autonomy and annual sunlight exposure were calculated and in the calculations, the colored areas represent the areas that are above the target level for sDA and sunlight exposure as %75 and 250 hours respectively. Without any shading device, sDA has the highest value as %82.14, however, the highest value which is exceeding the target value of 250 hours is also the scenario where no shading elements are used. Although there is a difference between the three models, it is seen that the room needs special configuration for the areas close to the window for sunlight exposure.

As the conclusion of the analysis of the single unit, it can be said that the overhangs have the effect to control the sunlight in the room. Shading panels which were removed by the user of the space is actually also effective to control the sunlight and create better uniformity in the indoor areas. However, since the building orientation enables to receive the light from northwest and southeast, every block and unit of the whole building should be analyzed individually in relation to the open spaces, courtyards, and surrounding buildings.

Conclusion

The form of the building is formed by the relationship it establishes with its surroundings in terms of scale and history, carrying the street life to the upper levels by providing uninterrupted circulations and it has led to the formation of the building and its facade with open spaces such as courtyards, semi-open spaces, terraces, balconies, shading elements. Although it was seen that some of the existing elements function in terms of sustainability, the whole building should be studied by using its existing potential. Shading panels that were removed should be brought back to use. Although courtyards provide daylight to the shops, overexposure in the space should also take into consideration for better use of open space for users of the space. Terraces or flat roofs can be used more effectively with solar panels and produce energy for buildings. The problems and potentials of the space should be identified and new definitions of spaces and functions should be made to gain the building back. The lighting design should be redefined according to the new functions and needs. Daylighting controls should be carefully studied and implied and they should go hand to hand with the artificial lighting need of the space. It is possible to achieve environmental, economic, and social sustainability with local-specific interventions from stakeholders and professions.

References

- Akin, C. (2020). Universiti Putra Malaysia Microclimatic Design Strategies In Mardin Vernacular Architecture. Alam Cipta, [online] 13(1). Available at: https://frsb.upm.edu.my/upload/dokumen/20200630134251Paper_7.pdf

- Alioğlu, E, F. (2000), Mardin Şehir Dokusu ve Evler,Türkiye Ekonomik ve Toplumsal Tarih Vakfı, Istanbul.

- Altuğ, E. (2007). AKM’yi Yakmayan, Yıkmayan (Ama Yeniden de Yapmayan) Bienalin Adrından Düşünebilmek, mimarist, İstanbul

- ArchDaily. (2014). Light Matters: 7 Ways Daylight Can Make Design More Sustainable. [online] Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/471249/light-matters-7-ways-daylight-can-make-design-more-sustainable

- ArchDaily. (2014). Light Matters: 7 Ways Lighting Can Make Architecture More Sustainable. [online] Available at: https://www.archdaily.com/564798/light-matters-7-ways-lighting-can-make-architecture-more-sustainable

- Aydin, Yusuf Cihat & Mirzaei, Parham. (2017). Wind-driven ventilation improvement with plan typology alteration: A CFD case study of traditional Turkish architecture. Building Simulation. 10. 239–254. 10.1007/s12273-016-0321-4.

- Deru, M., Blair, N. and Torcellini, P. (2005). Procedure to Measure Indoor Lighting Energy Performance. [online] Available at: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy06osti/38602.pdf

- drajmarsh.bitbucket.io. (n.d.). PD: 2D Sun-Path. [online] Available at: https://drajmarsh.bitbucket.io/sunpath2d.html

- drajmarsh.bitbucket.io. (n.d.). PD: Dynamic Daylight. [online] Available at: https://drajmarsh.bitbucket.io/daylight-box.html.

- GmbH, E. (n.d.). The next generation spotlight: The new Parscan! - Products | ERCO. [online] www.erco.com. Available at: https://www.erco.com/en/service/microsites/products/the-next-generation-spotlight-the-new-parscan-7339/

- Google Earth (2022). Google Earth. [online] Google.com. Available at: https://earth.google.com/web/

- Gzt (2020). Geç Modernleşen İstanbul’un ilk alışveriş merkezi: İstanbul Manifaturacılar Çarşısı. [online] Gzt. Available at: https://www.gzt.com/arkitekt/gec-modernlesen-istanbulun-ilk-alisveris-merkezi-istanbul-manifaturacilar-carsisi-3561579

- Lechner, N. (2009). Heating, cooling, lighting : sustainable design methods for architects. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- saltresearch.org. (n.d.). Salt Araştırma. [online] Available at: https://saltresearch.org/primo_library/libweb/action/search.do?vid=salt

- Sayigh, Ali & Marafia, A. Hamid, 1998. "Chapter 1--Thermal comfort and the development of bioclimatic concept in building design," Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, Elsevier, vol. 2(1-2), pages 3-24

- United Nations (2022). Sustainability | United Nations. United Nations. [online] Available at: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/sustainability